What Could Go Wrong? Dissecting and Refining your Primitive Archery gear.

I write an article like this every year in hopes of reaching new archers and hunters and helping them find success in the woods. It is my truest hope that the data I have collected from both my failures and successes will benefit the current and upcoming generations of primitive hunters. I have spent the last 12 or 13 years building, refining and hunting with primitive tackle. Being both a builder and a hunter of all primitive hunting implements: Bows, arrows, atlatls, and flintknapped stone projectiles, I have had the ability to refine, hone, and completely change my gear to find the successes we all long for while carrying a bent stick and stone tipped arrows into the woods. I have gone from incredibly crude equipment and bouncing arrows off deer, to now shooting pass through shots and watching animals fall over dead inside of 50 yards nearly every time I release a projectile. When I first got started there were very limited resources to learn how to make primitive weapons truly efficient, so I struggled through years of trial and error which has given me an extremely clear view of what consistently works, but also what does not. I had always said, even in those early years, when I finally figure this stuff out and get truly reliable and repeatable success that I fully rely on, I will always do my best to share that information with others. Are my ways the only ways? Certainly not. I know many folks have found some measure of success doing things I have specifically warned against. I have learned it isn’t so much about can it work, but rather does it work well time and time again. That is the essence of this article; to give people a guide of things to look for, to strive for, and also to avoid.

I think first we should really define what success is. While many would simply agree that just spending a day in the wood is a good day. Enjoying the great outdoors is in itself a success, but let’s really get down to the truth that when we go into the woods to hunt, serious hunters want to be packing an animal out when they leave. If we can boil that down even further, yes it is a successful hunt if you shoot a deer, track it for 3 hours and recover it 600 yards away. That is absolutely a success and every primitive hunter will find himself /herself in that situation if they stick with it. Many times peoples’ first successful primitive kills end up this way. A slight amount of penetration in a good spot, a long track job with a friend or 2 to help, and a very emotional long recovery. I always applaud the hard work that goes into these hunts as I have certainly been there many times myself. At this point in my hunting career, I really start defining a truly successful hunt by: Waiting for the perfect shot, delivering a perfect projectile, getting full penetration through the lungs or heart, and either watching the animal fall within sight, or following a very good blood trail 50 yards into the woods to an expired animal. That scenario is not the anomaly. It is the repeatable result of a refined hunter and his gear. I want all hunters to have the skill to track and recover a wounded animal, but I ultimately want hunters to be so refined that they too are consistently shooting double lung pass-throughs with stone points and watching deer or wild hogs fall within sight. Fast, efficient, and rewarding. Those are the perfect success stories.

When we think about modern store bought gear, we don’t really seem to have to worry if it will work. The basics of metal points, commercial shafts and standard bows are inherently deer killers right out of the box. If a guy orders a 45# laminated longbow, learns to shoot it well, shoots a set of wood, carbon or aluminum arrows with a commercial broadheads, the only real factor that determines success is where the archer puts the arrow. Do they have the accuracy under pressure? The patience to wait for a good shoot angle at a close distance? Those are all things that put the end result purely at the feet of the archer, and we have come to expect that simply picking up any wooden primitive bow, throwing and arrow off it with a stone point on the end will kill a deer. “Indians did it and it worked for them”. I have heard that so many times over but it is not as cut and dry as that statement. All folks are seeing is a fraction of an artifact that is not in any way in context to actual hunting. What is overlooked most often is the generations of teaching and refining extremely efficient gear in order to be successful and sustainable. When someone finds a clunky discarded stone point in a corn field and says “They used this to kill a deer”, they are missing a huge part of the story and also haven’t wrapped their head around the fact that the vast majority of points found in fields among flakes and broken pieces are simply discarded trash points. One that was made by a beginner, one that was a failed build, or one that maybe used to be much nicer and sharper but has been sharpened down over and over again until it was discarded as nothing but a trashy nub. It is only when you make a point like that, then shoot a deer, watch the arrow bounce off like it was shot with a rubber blunt, do you then realize that no, they didn’t actually shoot deer with that stuff. I have personally bounced crude points off of deer and I have also had multiple people through the years send me pictures of points and ask how they look, looking for accolades for their accomplishment in knapping. When I tell them that unfortunately those will likely bounce off, they aren’t happy with my answer and shoot it anyway. Then a couple months later send me a message saying, “You were right, that arrow bounced right off a deer this evening.” I never tell someone that their points are bad to try to put them down or discourage them, I always tell them they are doing great, on great path but need to get a bit better before launching them at a deer. Bouncing a point off of a deer puts people at a fork in the road. If they go left, they will never use a stone point again and will preach far and wide at how poor stone points work. If they turn right, they will do more research, get better at knapping, read articles like this one, and be out there again next time with a thin, sharp little nasty arrowpoint. I always want people to take the road to the right, and better yet, never even have to stop at that fork in the road of bouncing a point off of a deer.

The design of a stone point must be correct to truly find repeatable success. I personally shoot small points averaging 60-80 grains, very sharp little serrations, and a long needle sharp tip. Round nose points with thick cross sections are not good points for penetration. We have to accept that Stone points inherently have more resistance in penetration than a steel point. I have shown it over and over again that small points kill deer quick and penetrate very well. While I have been successful in killing game with larger points over 100 grains with much longer wider dimensions, I have also seen those large points fail to penetrate fully. If you combine that with another negative factor like a wobbly arrow, rough point to arrow transition or light weight bow, they may completely fail to penetrate vital organs at all. While Dr Ashby confirmed that more mass penetrates better, that does not entirely correlate with shooting stone projectiles. Stone is much less dense than steel so it takes a much larger point to get those very heavy weights. By increasing overall dimensions, you then also drastically increase the resistance of the point upon entry. The knapped edge of a stone point simply has much more resistance than a single honed edge of steel. A very simple test to do is to take a piece of leather and with a razor sharp metal broadhead, push the point through the leather. Repeat this process with a stone projectile and you will notice a significant increase in the energy it takes to penetrate. That doesn’t mean that stone points are ineffective. It simply means we have to approach our hunts and gear with a different mindset than we do with metal broadheads. True arrowhead artifacts are quite small, thin and sharp. The larger points that people find were used on larger and heavier atlatl thrown spears. In most cases, if you shoot an arrow with an atlatl point on the end, it simply will not penetrate well. Shoot one with a small arrowhead and you will see how well it penetrates comparatively. Modern man is under the misconception that the larger the animal, the larger the point it takes to kill it. That is actually quite opposite of the truth. While working with the Department of Anthropology at Texas A&M and UTC, we have shown many times through both practical tests as well as examining points from 13,000 year old megafauna kill sites, that smaller points are required for the largest of animals because a very large point more often than not fails to penetrate the axial skeleton (Rib Cage or Spine). If you read my previous articles you also saw that I took down a 1300lbs bison with a small Dalton style point delivered from an atlatl and spear. That point is smaller than the broadheads used by average modern hunters for deer hunting, yet very efficiently brought down a bull bison. The moral of the story is that small, thin, sharp edged, and needle tipped arrowheads are incredibly deadly and efficient. They reliable penetrate better than over sized points, especially ones with relatively rounded noses.

The edge of the stone point is also extremely important. A stone point isn’t “sharper than it feels”. If it doesn’t feel sharp enough to cut you, then it won’t magically cut a deer any better. Can you kill a deer with a dull point? Absolutely. Just like you can kill a deer with a target field point. That however isn’t a reliable and efficient method. A very sharp point will not only penetrate better but also cause massive hemorrhage and bring the animal down much faster. A dull point can actually slide by, or push vital organs out of the way on grazing blows without cutting them. Just like with a metal broadhead, you want your stone points scary sharp. When I sharpen my points, I feel the edge on the back of my thumb and often cut myself with a light touch. That is how sharp your stone points should be. The arguments that artifact points were not that sharp can’t truly be supported since artifacts are not only subject to erosion, but also again, often merely discarded junk, or shot and lost. Very rarely would a valuable arrowhead be freshly sharpened for the hunt, then left carefully on the ground for you to come find thousands of years later. You wouldn’t find an old aluminum arrow in the woods shot and lost 10 years ago and expect the broadhead to be shave sharp when you feel it. Now imagine finding a stone point from either 200 or 2000 years ago subject to countless cycles of water, wind and sand abrasion.

The transition from the point to the arrow shaft should be very smooth. I see a lot of people make the mistake of cutting a notch in the shaft, gluing their point in, then mounding sinew up around it. Rough transitions can impede or entirely stop penetration. The shaft should be tapered very cleanly and smoothly into the stone point and sculpted smooth with pine pitch. The sinew should be thin strands neatly wrapped to create a strong but very streamline profile. I tell new builders to gently slide their hafted points between their tightly closed fingers. If the transition slides right through without hesitation, then it is a good transition. If it hangs up or tries to push your hand backwards, then the transition is far too abrupt.

Arrow flight and weigh is extremely important. If arrows wobble or seem to fly with a yaw, then the energy from impact will be deflected away from the tip of the point. Arrows should straighten out in flight very quickly and hit perfectly straight into the target. Every amount of yaw, porpoising, or fishtailing will cause your arrow to lose energy upon target impact. Any displaced energy is just one more way to slow penetration. Arrow weight is also important. Heavier arrows may be slower, but they also carry more energy and momentum. Simply enough, longer arrows have more weight and stability in flight. Both are great attributes for hunting arrows. I personally shoot arrows around 30 inches in length and weighing in the 500 grain range. Pair that with a quick bow and sharp little arrow point and you will see fantastic penetration.

Bow performance does count for something. I have done many hunts, many penetration tests and have compiled enormous data and experience in how bow performance effects penetration. It doesn’t take a college graduate to figure out that heavier bows typically deliver more energy. There are in fact other variables that effect performance such as wood species, bow design, draw length, and limb mass. Without going super deep into that, we have to assume that the average homemade primitive bow is not a super performer, especially if we are running a very primitive design of a D shaped hickory bow around 50 pounds. I have seen some simple bows shoot very fast and others that are terribly slow. I have seen bows that shoot 130fps deliver pass-through shots, and ones that shoot 160fps fail to penetrate completely. Bow performance is not the sole factor in successful hunting. Simply shooting a heavier bow isn’t a solution for counterbalancing an inefficient arrow. Trust me, I know! When I was much younger and my arrows didn’t perform well, it was as simple as saying I needed a heavier bow. It made some difference, but in all honesty, the refinement of the arrow is what actually made all the difference in good penetrative qualities. All that being said, the bow is still an important variable. I really like to have bow that shoots at least a conservative 150 fps with a 500 grain arrow. That is a fairly achievable number for anyone shooting a 50-55 pound bow. I can and have been extremely successful with lighter weight and slower shooting bows with very well made streamline arrows, but at the end of the day, if you can bump up in weight or bow performance, that is just 1 more controllable variable to stack the odds in your favor.

Draw length is another factor worth touching on. A longer draw length has a longer power stroke and will transfer more energy to the arrow. Now, that does in no way mean that you cannot be successful with a short draw. I am a testament to that. I only shoot about a 22-23 inch draw depending on the bow style I am shooting. The difference is, I am also shooting a bow tailor made to be a good performer at my specific draw length. A long 68 inch bow that is 50# at 29” draw will be terribly slow an ineffective if only drawn to say 25 inches. Not only will the weigh drop down to about 38# at your 25 inch draw length, but the limbs of the bow will not have the potential stored energy that a properly sized bow would have. Since I shoot 22 or 23 inches, many of my bows are in the 52-56 inch long range and most importantly, the weight I speak of is measured at my true draw length. Remember, just because a bow is listed at 50# doesn’t mean you are actually drawing it to 50#. Correctly measuring your draw length is incredibly important. I have seen many people draw a bow back much further when measuring their potential draw length, only to draw significantly shorter when they are actually shooting an arrow. This is much more common than you think. I don’t care how insistent you are that you draw 28”, always do a very simple test to make sure. Mark an arrow with 1 inch increment and shoot it normally over and over again. Do not try to stretch your draw out. The important thing is to shoot completely naturally. It does not make you any less of a man to have a shorter draw length and you will only be hurting yourself by trying to stretch an extra inch or 2 out of your draw during measuring if you only resort back to drawing less when you shoot naturally. When shooting 6 or so shots naturally and unbiased to your proposed draw length, have a friend watch and record silently to what line you drew to every time. Then after 6 or so shots, go measure from the inside of the arrow nock to the place you actually drew the arrow to, flush with the back of the bow. That will be your true shooting draw length. Static drawing a bow 30 inches means nothing if you are only drawing it 27 inches when you actually shoot. You may be drawing the same exact number both before and after shooting, but I hear so often when people come back and tell me that they were insistent they drew a 28 inch draw because they had the archery range measure it. They then conducted my test and realized they are actually shooting several inches shorter than they ever realized. That has been the cause of many people getting poor arrow penetration. They think they are shooting 50# at 28” but in reality they end up only shooting 42, 40, or 38 pounds at their true draw length, so definitely check that out before crossing the bow weight variable off the list.

I think the biggest takeaway should be that it is not the bow, not the arrow, nor the point that makes a successful hunting set. It is a culmination of refining and maximizing all the variables that you have control over. If you start off with a 1-10 scale and consider numbers 8 -10 to be maximum penetration of big game, then take away 1 or 2 numbers at a time for every variable not refined, you can start seeing the overall performance of a hunting set going down considerably. If we take 1 point away for a light bow, 1 point away for a light arrow, 1 point away for a wobbly arrow, 2 points away for a abrupt transition, 1 point away for a point that just isn’t very sharp, and 2 points away for a rounded, blunt nose point…. Then we are down to a 2 out of 10 for efficiency. That is how we end up bouncing a point off of the side of a deer even when we did everything else right like waiting for the right shot, broadside at 10 yards, and put the arrow right on the ten ring. Yet here we are with a deer running away with either your arrow laying on the ground, or only sticking in the deer 2 inches and it’s hanging down flopping as the deer runs off never to be seen again.

The important thing is to scrutinize and refine every aspect of your primitive hunting gear. Primitive doesn’t mean crude and haphazard. Primitive gear can be, and historically was, extremely well made and efficient in the practice of taking the game they were hunting. I truly hope you took something very valuable from this article. I want to see everyone out there hunting with 8 out of 10 or 10 out of 10 hunting gear this year. Whether you make your own gear or buy it from someone else, always take the time and responsibility to scrutinize it and go over it. While anyone can make and/or sell a bow, arrows, and stone points, not everyone has the experience in true successful hunting to make sure that they are building highly refined hunting implements, purpose built for phenomenal tales of success. Never leave that to chance. Go back over this list and check for all those things listed above and I am sure you’ll be knockin’ ’em dead. If you read this article and found education or inspiration, then follow me @HuntPrimitive on Instagram or Facebook and make sure you tag me in your successful hunting pictures this year. I would love to see them! – Ryan Gill

KnapEasy / Tool Combo kits

$104.00 – $175.00Price range: $104.00 through $175.00

KnapEasy / Tool Combo kits

$104.00 – $175.00Price range: $104.00 through $175.00

KnapEasy Rock

$32.00 – $166.00Price range: $32.00 through $166.00

KnapEasy Rock

$32.00 – $166.00Price range: $32.00 through $166.00

Thonotossa Knives

$119.00 – $159.99Price range: $119.00 through $159.99

Thonotossa Knives

$119.00 – $159.99Price range: $119.00 through $159.99

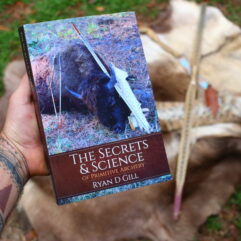

The Secrets and Science of Primitive Archery (Volume 1)

$29.99

The Secrets and Science of Primitive Archery (Volume 1)

$29.99

Flint Knapping Kits and Rock Combos

$99.95 – $208.98Price range: $99.95 through $208.98

Flint Knapping Kits and Rock Combos

$99.95 – $208.98Price range: $99.95 through $208.98

Walnut- Deer Skinner Stone Knives

$119.00 – $159.99Price range: $119.00 through $159.99

Walnut- Deer Skinner Stone Knives

$119.00 – $159.99Price range: $119.00 through $159.99

Caveman Shirts

$18.49

Caveman Shirts

$18.49